Damea Comments on the Medicare ACO Proposed Rules:

- Mike Barrett

- Aug 20, 2019

- 11 min read

Updated: Dec 19, 2019

It is clear that CMS, OMB, and the other constituencies within the Administration have worked tirelessly to improve the Medicare Shared Saving Program and to protect the Medicare Trust fund while balancing the needs and wants of both the taxpayer and beneficiary. We applaud your efforts.

Before we make any specific recommendation, we would like to point out an area of general concern. In the push to greater risk, a number of ACOs will undoubtedly drop from the program which may result in beneficiaries treated by those providers to lose the underlying quality improvement programs and initiatives. Further, as the Shared Savings Program narrows it’s focus and assignment rules we are concerned that some of the most fragile and poorly coordinated populations are losing quality improvement programs. This is specifically concerning for beneficiaries in skilled nursing facilities. With CMS excluding SNF patients from assignment, this population that could so significantly benefit from coordination are left out of the movement toward value vs. volume.

The expansion of the three year contract cycle to five years is of great concern. The 2012/2013 starts have been either sheltered from consequences or put at a significant competitive disadvantage. As noted in the NPRM, several ACOs received windfall profits, our review of the 2012/2013 starts (all of them) suggests that some of the most efficient provider groups partnered with CMS as early adopters, only to be put at a competitive disadvantage when the regional benchmarking formulas where deployed to later entrants. Further, it is not likely that the regulatory landscape will remain consistent over the next five years. History demonstrated that the program is still maturing and significant advancement in regulation continue to be likely. Shelter from consequence or competitively disadvantaging superior performers is not in the best interest of CMS, beneficiaries or the taxpayers. We suggest that CMS either shorten the contract cycles or provider for immediate update for regulations (all MA provider contracts allow for such) on the annual anniversary of the contract effective date.

Our specific suggestions focus on making quality performance THE mission critical determinant of success, followed closely behind by economic efficiency. In general, those ACOs that demonstrate both high quality and lower costs than their regional rivals should be allowed to bring their better product result to the market in a more forceful and deliberate fashion. We have modeled out the full cost, variable cost and net economic impacts of both the current and proposed regulations and find they net-net to be muted significantly in facility based ACOs because of the variable vs full cost elements of excess utilization. Gain and loss sharing rates alone will be insufficient to drive transformation of the health system to assure liquidity of the Medicare Trust Fund. Allowing the market forces of a better product to guide beneficiaries in their care decisions will have greater impact on the net-net economics of the large systems and maximize the liquidity of the Medicare Trust Fund.

There are several areas which would benefit from greater effort, clarity and precision than that described in the NPRM: These are:

Substantively increase beneficiary alignment with high quality low cost ACOs

Unify quality measures between Medicare Shared Savings Programs (the Shared Savings Program) and Medicare Advantage (MA).

Use tools and techniques successful in MA to further enable the Shared Savings Program.

Expansion of AIPBP type programs to the Shared Savings Program.

Vehicle for Medical Necessity Determination and Claim Appeal for the Shared Savings Program.

Encourage beneficiaries to align with high quality and low cost ACOs:

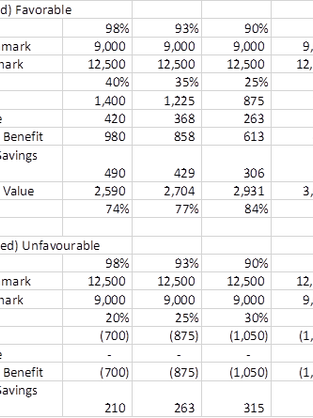

CMS should link the constraints of risk adjusted regional benchmarking to the quality score which will reinforce the imperative of high quality and lower cost care. Further, we suggest that a significant portion of this value be provided directly to the beneficiary. Our analysis indicates that for the highest performing ACOs (table below) an amount equal to 30% of regional benchmark adjustment value (after applying the regional/historic weighting factor) would provide the beneficiary a noticeable and tangible benefit that would result in greater alignment with the very best ACOs. This incentive could be in the form of either reduced copays/coinsurance or a rebate on Part B premiums will directly reinforce the goal of moving our health care system to high quality and low cost.

In the table below is the example of expanding reginal to historic benchmark value that should be shared with beneficiaries for the highest quality and lower cost ACOs. By including the beneficiary in the value generated by very high quality ACOs which demonstrate lower costs, significant market forces are brought to bear for the benefit of the Trust Fund and the beneficiary. CMS could utilize several options to administrate this element. Most easily administered is the reduced cost shares as they could be applied at the time of service when the beneficiary utilizes a provider in the ACO. Either by the ACO provider which is allowed to waive certain cost shares, or in the adjudication and pricing of a claim. Similar to the AIPBP process providers would contract with these ACOs as either preferred providers/suppliers or actual ACO Participants. The ACO would choose to the waiving of cost share or having the increased amount paid (in the calculation of cost share in a claims process) from the shared savings payment. We believe most ACOs would utilize the waived cost share by the provider option vs. increasing the amount paid by CMS. This would further encourage the beneficiaries to use ACO contracted providers.

Slightly more problematic in administration, is the rebate of some portion of the Part B Premium. Significantly enabled by prospective voluntary alignment, it would be reasonable for CMS to require voluntary prospective alignment in order for the beneficiary to access the Part B Premium rebate.

The costs paid or premium rebated would become ACO costs and reconciled to prospective estimates in the final reconciliation. It seems to be in Trust Fund’s best interest to engage the beneficiary more directly in selecting those provider systems that have empirically demonstrated superior performance. The application of this element would be in either year 2 (based on the underlying quality score vs. report only value) of a new the Shared Savings Program contract or upon renewal of existing ACO entity. These values would be updated annually to reinforce continued process improvement.

In the table below, the Trust Fund retains no less than 60% of the value of low cost providers, and the beneficiaries may gain 12% (highest weighting x 30%). The efficient health care system would then have a gross savings opportunity of 28% of the differential prior to the application of the sharing percent with CMS. To further incent ACOs to take risk, this factor would only be available to Level E or Enhanced ACOs. Fully realized the Trust Fund retains 60% initially, then either an additional 7% (Enhanced) or 14% (Level E) of the regional vs. historic variation. This formula limits any windfall profits, provide more incentive for successful ACOs to move to risk and beneficiary to align with the high quality, lowest cost provider systems, as well as, blunt the incentive of the lowest cost ACOs to move to Medicare Advantage. Lastly, the market force implied within this structure should cause all providers in the geography to improve quality and lower costs.

Suggested Quality Score, Constraint, and Weighting

It is not likely that an ACO with quality scores below 86% that was significantly above regional average would stay in the Shared Savings Program. Further, the providers within the poor performing ACO would see their relative cost to beneficiaries increase significantly, they are after all in a less valuable system of care.

Example Calculation:

Unifying Quality Measures between Shared Savings Program and MA:

There should be fewer measures which are published on a roadmap for implementation for both programs. Through the use of market forces in both programs, success on each measure would be all but assured. The differing standards of compliance and different measures serves only to confuse the physicians and their staff, as well as, spread scant resources yet thinner across a broader waterfront of activities. With a roadmap of measures and performance, organizations would focus their energies in achieving these metrics is systematic and deliberate fashion. As measures are added, older measures should be phased out with larger thresholds, yet more significant penalties for a lack of performances.

For example, if the super majority of contractors have achieved a 95%+ score the upside value of the measure would be retired while the downside would be retained for some period to entrench the process as a standard. The penalty for sub 90% score could be a decrement of 5% of either net payment level in MA or benchmark in the Shared Savings Program. Poor performers would suffer a significant consequence, while superior performers monitor maintenance and move incremental resources to emerging measures. This decrement would be in addition to any regional benchmarking decrement outlined above.

Tools from Medicare Advantage (MA) to enable Shared Savings Program.

The Shared Savings Program has created a Pandora’s Box issue related to the physician community. Historically, very few physicians had direct empirical evidence of their relative or absolute cost and quality. Now, most physicians in an ACO know their panel cost, their quality score and the averages of the ACO now know their absolute and relative economic performance. The high performing physicians are now decidedly motivated to balance their efforts in favor of MA. Unfortunately, this would not really expand savings to the Trust Fund and would serve only to reduce options and choices for the beneficiaries. The better solution for all constituencies is that MSSP more closely resemble MA, more organization seeking higher savings.

The improvement in the Shared Savings Program rule comes in at least two areas. First it he application of risk adjustment to benchmarking. We have seen the implementation of ICD10 increase the specificity diagnostic precision and hence risk score – coding intensity and both MA and Shared Savings Programs have made initial adjustments. We should note that using coding intensity for the sole purposes of revenue enhancement borders on Abuse as it relates to FWA regulations. In the era of accountability, accurately and completely describing the diagnostic and health status of the population is well within an expected set of core competencies. Further, clinical information improvements from the greater specificity (goal of ICD10, 11 and SNOMED) will yield important insights over the intermediate and longer term. These are extremely important policy issues that will benefit from increased support.

Allowing risk adjustment to move more freely, while still normalizing back to a national 1.0 score provides delivery systems with substantive incentive to increase specificity, while protecting the Trust Fund from “gaming”. Applied in a zero-sum fashion, those ACOs that continue to document and code in a substandard fashion would bear the consequence of inferior administrative skills and ability. Inferior documentation and coding efforts degrade the ability of the improved information set to provide insights to the entire system. There is a real system consequence for this substandard information set, it is only appropriate that a consequence flow to substandard information providers. This should be applied to both MA and the Shared Savings Program consistently.

Second is the sharing rates of savings within the programs. In a fashion similar to the MA STARs program, Superior performances should be rewarded more directly economically and with some portion rewarding beneficiaries using the high quality/lowest cost delivery system. For example:

Downside sharing would be similarly impacted. The higher the quality score, the lower the loss sharing combined with the regional benchmark suggestions above, the high quality low cost system would have an advantage that would drive a favorable competitive response from the other delivery systems in the area. As the other delivery systems converge, CMS is harvesting savings as the economics become level at a lower cost and sharing rate, data specificity is driven to a very high level, and beneficiaries now have more choices in high quality and low cost healthcare.

Expansion of AIPBP to the Shared Savings Program:

ACOs face enormous working capital burdens. AIPBP may provide some relief from these burdens in the form of an interim cash flow. To be certain, this program should only be extended to MSPP contractors at level D or higher risk and would be 100% additive to the downside risk exposure otherwise calculated in the program. Further, expected payments would have to expand the financial guarantee otherwise provided, to assure the Trust Fund is not at risk for the payments provided which are beyond the financial guarantee provided by the ACO we recommend 50% of the expected amount be added to the financial guarantee. To protect the Trust Fund yet further, if the experience through June 30 of the performance year indicated that there would be a deficit (prospectively assigned ACOs) the payments would be suspended and held by CMS. Lastly, if the ACO where to have expenses above the calculated benchmark, 100% of the AIPBP funding would be recaptured by CMS before any sharing percentage would be applied.

There are several benefits beyond simply cash flow that would accrue to the beneficiaries, Trust Fund, and CMS. These are

Providers contracted in the AIPBP would be more deeply integrated for customer service, care coordination, medical appropriateness, and timely information sharing.

ACOs would be incentivized to provide educate for all ACO Providers on who are the AIPBP providers, install processes and programs to improve access, monitoring compliance, expanding information sharing with AIPBP providers for quality improvement and consistent health care outcomes.

ACOs would take much greater interest in the performance of all providers treating their assigned beneficiaries.

Post-acute providers and treatment pathways would be investigated deeply.

Vehicle for Medical Necessity Determinations and Claims Appeal:

There needs to be a vehicle to engage the health care providers beyond submitting a set of documents to the OIG for a fraud investigation. Not all events raise to the level of intentional fraud. Some events are simply clumsy data input, others may be less than energetic pursuit of lower cost alternatives or seeking prior treatment records. Further, most MA contractors provide this vehicle to their downstream risk/gain sharing provider groups. This is not an unknown science or administrative process.

None the less, these determinations are closely tied to quality measurement and medical necessity is extremely important and could be a significant driving force in improving both total quality and value in the U.S. health care system. Stunningly, I have had to argue with providers regarding the statement that “there is no such thing as medically inappropriate necessary care.” To put the point on this statement is the denial rate for “Medically Unnecessary (MU)” at the Medicare Advantage health plans. Even after appeal to independent review, it is not uncommon to find MU denial rates in excess of 10%. Imagine a product that would survive a 10% error rate, yet we see it ever day in healthcare.

It is somewhat disingenuous for CMS to contract with the Shared Savings Program entities (ACO) “…accountable for all care…” yet not provide a vehicle to exercise that accountability for the beneficiaries assigned/assignable to the ACO. I have personally attempted to contact several Medicare Administrative Contractors on several occasions and NEVER received a return phone call from a single one, yet at the time I was managing more the Shared Savings Program contracts than any other contractor.

Providing a vehicle for ACOs to confront these issues would provide two very important benefits. In the extreme short term, there would be some economic savings harvested by both the Trust Fund and the ACO. Very quickly, service providers would seek to engage ACOs to comply with quality programs, care navigation standards, updated treatment pathways, and care coordination both pre and post treatment. Care coordination would rapidly displace the short-term activity of denying payment post service as “Medically Unnecessary.”

It is expected, indeed only proper, to allow service providers the venue to appeal the determination. Such determinations would not likely be abused, as there is no cash value accruing to the ACO as there is in Medicare Advantage.

Perhaps no other event would transform the health care delivery system more than allowing ACOs the ability to review care for medical necessity.

Conclusion:

We suggest CMS consider the vulnerable populations in nursing facilities so as to not be inadvertently carved out of quality improvement and care coordination processes.

The ACO contract should allow updated regulations to apply immediately versus upon renewal so that the competitive landscape is not perverted unintentionally.

Make quality the center point of the ACO program by linking multiple economic elements to the quality score.

Bring the beneficiary into the result of superior performance and allow market forces to drive success and failure of an ACO and delivery system.

Unify quality measures with a road map so providers can anticipate and appropriately deploy the limited resources.

Reinforce improved clinical information gathering by linking benchmarks without limitation yet rescale the national impact to 1.0 risks scores.

Apply lessons from Medicare Advantage where using competition has driven STAR score and quality improvement programs.

Expand the AIPBP program to Level E and Enhanced ACOs. CMS gains a portion of these savings, while providing expanded resources to ACO for greater investment and improvement.

ACOs should have greater authority to exercise their accountability for the quality outcome and economic costs of the care provided to the beneficiaries. There needs to be a direct vehicle to determine prospectively and/or retrospectively medical neccissity.

Comments